Architectural Record Features Yale Colleges

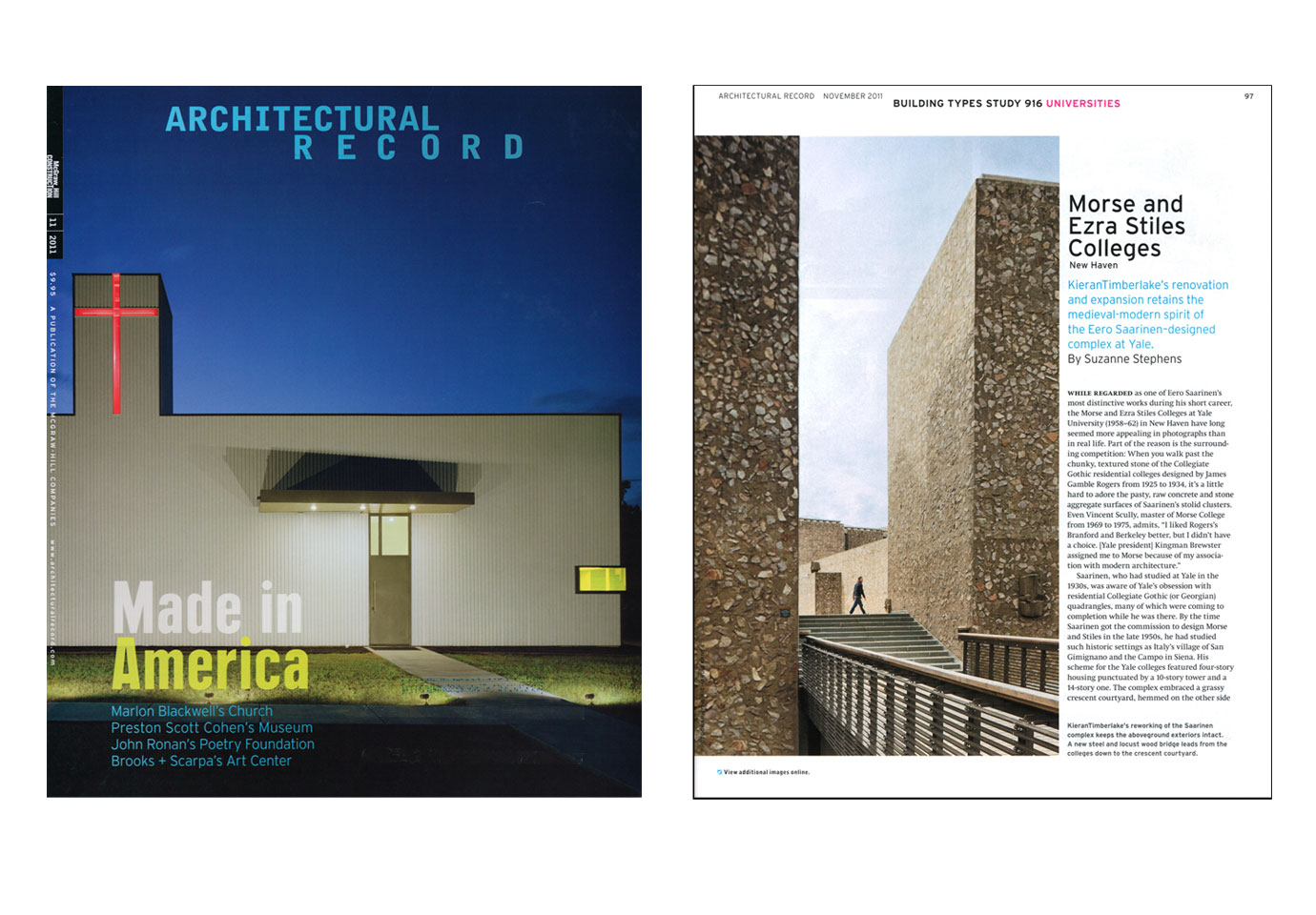

The November 2011 issue of Architectural Record covers the transformation of Morse and Ezra Stiles Colleges at Yale University.

KieranTimberlake's renovation and expansion retains the medieval-modern spirit of the Eero Saarinen–designed complex at Yale

By Suzanne Stephens

While regarded as one of Eero Saarinen's most distinctive works during his short career, the Morse and Ezra Stiles Colleges at Yale University (1958–62) in New Haven have long seemed more appealing in photographs than in real life. Part of the reason is the surrounding competition: When you walk past the chunky, textured stone of the Collegiate Gothic residential colleges designed by James Gamble Rogers from 1925 to 1934, it's a little hard to adore the pasty, raw concrete and stone aggregate surfaces of Saarinen's stolid clusters. Even Vincent Scully, master of Morse College from 1969 to 1975, admits, “I liked Rogers's Branford and Berkeley better, but I didn't have a choice. [Yale president] Kingman Brewster assigned me to Morse because of my association with modern architecture.”

Saarinen, who had studied at Yale in the 1930s, was aware of Yale's obsession with residential Collegiate Gothic (or Georgian) quadrangles, many of which were coming to completion while he was there. By the time Saarinen got the commission to design Morse and Stiles in the late 1950s, he had studied such historic settings as Italy's village of San Gimignano and the Campo in Siena. His scheme for the Yale colleges featured four-story housing punctuated by a 10-story tower and a 14-story one. The complex embraced a grassy crescent courtyard, hemmed on the other side by Tower Parkway. Saarinen intended the complex at the western edge of campus to be a porous village, with pathways allowing more freedom of pedestrian movement than found in the enclosed quadrangles. But by the late 1960s, with student unrest, town-gown problems, and the admission of women, the village turned into a castle keep under lock and key.

Rather than resort to stone or brick, Saarinen built the colleges of poured-in-place concrete. He mixed in a large-scale, crushed granite so the aggregate would have a flinty, hard, angular quality. Yet the resulting exterior, notes Scully, is “kind of soft and flat-looking, like adobe.” The battlement massing was unforgiving. Scully recalls, “Paul Rudolph [chair of the School of Architecture from 1958–67] used to say it looked like a set for Ivanhoe.”

Today the modern-medieval fortress has softened with age—although it could stand a bit more ivy. When Yale decided it was time to renovate and expand the colleges, it hired KieranTimberlake Architects (KTA) to remedy problematic features that had existed since 1962. One of KieranTimberlake's assignments was to reconfigure the living quarters for the 500 students. (Each residential college also includes a Saarinen-designed house for the master, plus accommodations for each dean and two fellows.) Saarinen, in accordance with a wish expressed by a student survey, had designed the rooms as stand-alone singles. But over the years, it became clear that the students wanted single rooms that were integrated into suites, typical of Yale's other residential colleges. KTA, which already had redone Berkeley, Silliman, Pierson, and Davenport Colleges, carried out the mission with jigsaw-puzzle precision.

In its 285,000-square-foot renovation and expansion, the Philadelphia firm preserved the concrete and stone exterior but added 25,000 square feet of new construction underground. In doing so, KTA reclaimed basement areas and created a two-level addition extending underneath the crescent courtyard on the northwest side of the complex. Here now are new social and recreational spaces—a theater, as well as arts, dance, exercise, and music studios—that budget cuts hobbled in the original. “Putting in foundations and waterproofing was a structural tour de force,” says KTA's Stephen Kieran. “Conceptually, we poured forms and spaces like lava under the existing buildings and let them flow out.”

Continue reading